Personality and skills link

Can and How Can Cognitive Ability Tests Help Diagnose a Candidate's Personality?

|

Various types of personality tests are popular tools in the world of employment screening. Many employers place great importance on the personality of their employees, and ask recruiters to identify employees who are reliable, responsible, committed to their work, proactive, pleasant, able to work in a team, and more. Employers indicate that cognitive abilities, such as numerical ability, spatial ability, and memory, are not central considerations in selecting their employees, despite the fact that research has consistently found that cognitive ability tests help in selecting successful employees (want to know why? Read the article "The Purpose of Psychometric Aptitude Tests"), and even surpass personality tests in predicting which employees will be more successful and which will be less successful. In accordance with "customer demand", the world of employment screening is heavily engaged in ways to provide the employer with good tools to assess the candidate, with the aim of identifying reliable, responsible, committed, service-oriented employees or any other personality aspect important to the employer. |

The history of personality tests began with projective personality tests, and in recent decades has moved to self-report questionnaires based on broad personality traits (read here about the different types of personality tests - "Summary of Personality" tests). Projective tests ask the person to react to presented images, complete sentences, tell stories, and draw pictures. Self-report questionnaires are questionnaires in which the person is asked to tell about themselves (self-report). There are very significant differences between the task required in filling out a personality questionnaire (telling about yourself, drawing a picture) and the tasks required in the world of work. Therefore, it is sometimes difficult to draw conclusions from the results of these tests about a person's personality and their coping in the world of work (more details can be found in the article "Why Measurements of Broad Personality Dimensions Do Not Predict Job Performance Well").

In contrast, ability tests usually ask a person to do something. The task required of the examinees is similar to tasks they will be required to do in the actual work: solve problems, manipulate information, cope with task load, work under pressure, manage time, and more. Therefore, if we could extract personality information from cognitive test data - we could diagnose the candidate's personality better, and help employers identify the responsible, committed, stress-resistant (and so on) employees they are looking for. Cognitive ability test scores are related to some extent to the individual's personality, as will be detailed below; but more importantly - the style of coping with cognitive tests may indicate certain personality characteristics, and this is what we will focus on in this article.

The Connections Between Cognitive (Intelligence) Tests and Personality Tests

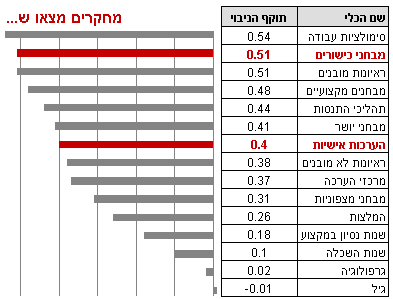

For many years, the world of psychological research regarded intelligence and personality as two separate constructs, each independently affecting a person's performance on tests, in studies, at work, and in life in general. However, over the years it has become increasingly clear that these two components cannot be separated. Research has shown that there are certain connections between personality traits (especially the Five Factor Model) and performance on cognitive tests. The leading trait in this context was found to be openness to experiences, which is most strongly related among the five factors to performance on cognitive tests. They also found a connection to conscientiousness, emotional stability, and a weak connection to extraversion (sources: Ackerman & Heggestad, 1997; Moutafi, Furnham & Crump, 2002).

At the basic level, we can see that both personality and intelligence affect an individual's performance. For example, perseverance, which is a personality trait, affects an individual's performance on a cognitive test: when a test-taker with high perseverance encounters difficult questions on a test, they will try to cope with them despite the difficulty; on the other hand - a test-taker with low perseverance will give up much more easily. It is likely that the first person will manage to achieve a higher score on the test than the second person, even if their true ability is exactly the same. On the other hand, intelligence may affect scores on personality tests if the task given to the person is difficult (for example - words in a high language, complicated instructions, etc.). People with high intelligence will manage to achieve scores that express their personality more accurately than people with lower intelligence, who had difficulty understanding or performing the task.

Allik & Realo (1997) found that people who differ in their level of intelligence may not differ systematically in their personality, but they use their intelligence for different purposes. People with low levels of intelligence focus on seeking sensations and fantasy life, while those with high intelligence use their intelligence for emotional regulation and managing their emotional life.

Chamorro-Premuzic, & Furnham (2004) explain two main connections found between personality traits and performance on intelligence tests. Low emotional stability may lower an individual's performance on tests, due to stress or anxiety from the test situation. Emotional stability (neuroticism) is defined as a general tendency to feel negative emotion such as sadness, fear, shame, anger, guilt, etc. People with high levels of neuroticism are more vulnerable to psychological distress and have a less adaptive coping style in stressful situations. The test situation, especially an employment screening test, is a situation laden with pressures. People with low emotional stability will exhibit less adaptive coping with the situation, and will not manage to demonstrate the true level of their intelligence.

Extraversion leads to a fast work pace, which affects test performance. Intelligence tests are usually time-limited. When a person manages to work at a faster pace, their scores on tests are higher than another person with a similar level of intelligence, but with a slow work pace.

But beyond the impact on scores, the question arises whether personality can affect the development of "true" intelligence (as opposed to a test score, which can deviate from the "truth" to some extent)? And vice versa - can intelligence affect the development of "true" personality? For example, one can speculate that more intelligent people accumulate more positive experiences around tests (which are very common in Western society), and thus their sense of competence and self-confidence is indeed higher than others, who experience difficulties and failures in cognitive tests. From the other direction, the personality trait of curiosity may increase a person's level of intelligence, through which they learn, explore and develop their thinking skills.

Chamorro-Premuzic, & Furnham (2004) explain that openness to experiences and intelligence are related through an individual's motivation to learn and expand their intellectual world (as well as emotional, values, and more). The personality trait "openness to experiences" refers to a person's tendency to actively seek experiences for their own sake, and indicates complexity of mental life. The trait is related to active imagination, sensitivity, alertness to inner feelings, preference for variety, intellectual curiosity and creativity. It makes sense that people with a high level of openness to experiences, who actively seek new experiences, will also seek intellectual experiences. The extensive experimentation with intellectual experiences, from logic puzzles to various philosophical and academic discussions, sharpens an individual's thinking skills and expands their intelligence, especially crystallized intelligence (which can be explained in the article Crystallized Intelligence and Fluid Intelligence.

Finally, certain studies have found a negative (inverse) relationship between conscientiousness and crystallized intelligence. The rationale, as explained by Moutafi, Furnham & Crump (2002), is that people with low levels of intelligence need to develop high levels of conscientiousness (including traits such as effort investment and thoroughness) in order to succeed in competitive Western society, while people with high levels of intelligence tend to rely more on their natural talent than on effort investment. The trade-off between effort and natural talent leads to people from both extremes (very talented or very hardworking) with a reasonable level of the other variable (normal investment level or normal intelligence, respectively) can succeed equally in cognitive challenges facing them.

Personality Characteristics Arising from Work Style in Cognitive Tests

Beyond the possible connections between the two characteristics (personality and intelligence), the question arises whether it is possible to utilize the many aptitude tests that job candidates take in order to learn about their personality. Aptitude tests have many advantages over common personality tests, as mentioned. Ability tests usually ask a person to do something. The task required of the examinees is directly related to the latent construct (for example: problem analysis) and similar to tasks they will be required to do in the actual work: solve problems, manipulate information, cope with task load, work under pressure, manage time, and more.

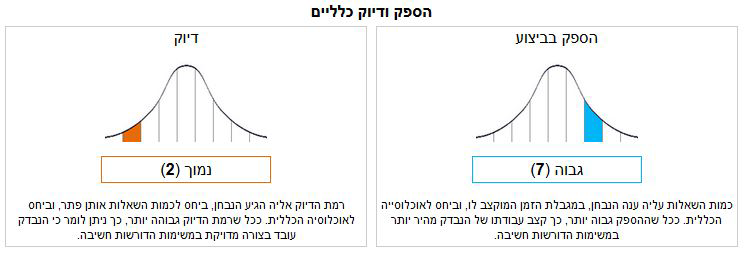

Aptitude tests have additional advantages: the multiplicity of tests allows seeing the examinee in many "opportunities", and over a relatively long period of time. Computerized tests allow for extensive and accurate collection of information, such as response time, changing answers, measuring breaks, and more. In addition, they are objective and absolute and this gives an advantage over subjective and relative assessment centers (the candidate is evaluated in relation to the group in which they are).

But the main advantage is that the person does something and not just talks about themselves. They can testify about tomorrow that they are considerate and planned and invested, but aptitude tests with low time utilization, careless work and more - will tell the truth...

First Example - Balance Between Output and Accuracy in Work

What can be learned about the personality of this examinee?

The output measure represents the average work pace of the examinee in all the cognitive tests they faced. That is - we can conclude that this is a person with a fast work pace. Seemingly, this is not a personality conclusion, but we can certainly see that the fast work pace is related to the personality trait "activity": people with a fast pace and movement, energetic and needing to be busy. This trait is part of the superordinate trait "extraversion", which belongs to the leading personality model in the world of work - the Big Five model.

The accuracy measure represents the extent to which the examinee's answers were correct. We can see that the examinee showed a relatively low level (compared to others) of correct answers. This is a measure that indicates their thinking abilities, and seemingly - it appears that they are low, and therefore did not answer correctly the questions presented to them.

When we look in a combined way at these two measures, high work speed but low work quality, several possibilities arise related to the examinee's personality.

1) This is an energetic person, who tends to work quickly, but their cognitive skills are low. From a personality perspective, it can be concluded that they do not balance well between their work pace and investment in tasks, within the limitations of their thinking ability. It is likely that if they worked a little slower, invested more effort in each task they encountered - their work quality would improve.

2) A second possibility is that this is a person with somewhat impulsive characteristics, who emphasizes work speed, completing tasks, "checking off" the task list, and does not give sufficient importance to the quality in which they perform the tasks. They cope well with task load, and seemingly will complete the tasks given to them, but when we examine their quality, especially as the task becomes more complex - we will be disappointed with the quality.

3) It may be an examinee who disregards the assessment, who thinks it is not important, and therefore just wants to finish with it. We can check this by examining another data point from the cognitive tests, which is their time utilization percentage: if they did not utilize all the time at their disposal, it is likely that this is disregard for the assessment and a desire to finish it without extra investment. We can infer from this how they will react to tasks that are "dropped from above", which they do not understand their importance and necessity - they will tend to want to "clear the table", declare "I'm done" and be less interested in meeting the quality in task performance.

Second Example - Personal Style in Dealing with Persistent Difficulties in a Test

What can be learned about the personality of this examinee?

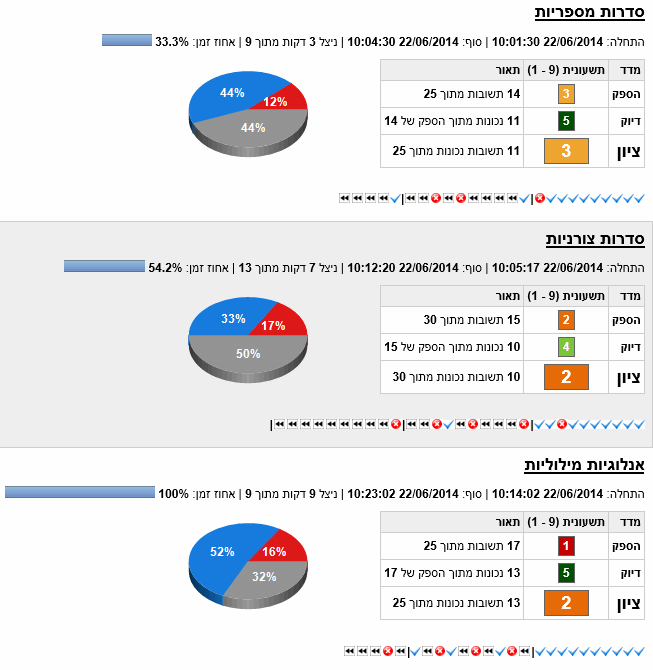

The examinee took three tests, in two of them she received a relatively low score - 3, and in one a slightly higher score - 4. We see that she is characterized by a relatively slow work pace (her output percentiles are 1-3). Seemingly, it can be concluded that this is a person with a relatively low work pace. But, when we look at her response pattern we see a different picture:

In two tests she utilized only a small part of her time (32% in numerical series, 58% in shape series), and yet she "didn't manage" to finish the entire test... How is this possible? This pattern tells us about the examinee's personality. Why did she choose not to utilize the time allocated to her to deal with the problems?

1) She got tired. Maybe because she had already done many tests and didn't have the energy. If we examine the next test she did (verbal analogies) we see that she actually had energy... In this test she utilized all the time. And she didn't take a break between tests to refresh and gather strength (note the start/end time of each test).

2) She gave up. She had time to complete more questions, but she didn't do it. She made two choices:

a. She chose to skip questions she didn't know, and leave them unanswered (for example - questions 12,13,14,15 in numerical series), apparently because she didn't know for certain what the correct answer was. There is a choice of the examinee here, she preferred to leave the questions unanswered rather than answer a question she wasn't sure about. Why? Because she is a perfectionist = if it's not perfect, then don't do it; because she is very afraid of how she will be perceived by others = if I make a mistake then they will think I'm stupid.

b. She chose not to invest additional effort in questions she didn't know in the first round, and preferred to move on to the next test. This indicates her self-confidence (low) = there's no chance I'll succeed, so why try and make an effort on it?; it also indicates the low ability to cope with obstacles and difficulties = if it's hard, it's better to leave it and move on.

In Summary

The ability of diagnostic and measurement tools to make cross-references and point out personality characteristics from aptitude tests and vice versa is already here, we need to translate the existing knowledge into the right algorithms and implement them in computerized screening systems.

It's important to remember that every measurement tool has advantages and weaknesses, so we should be careful not to rely on a single measurement tool. We need and can extract from diagnostic-screening tools information also on traits or skills they were not intended for, and together, when we look at the full picture, it will be easier for us to choose the most suitable candidate for the role.

Sources:

Ackerman, P.L. & Heggestad, E.D. (1997). Intelligence, personality and interests: Evidence for overlapping traits. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 219-245.

Allik, J. & Realo, A. (1997). Intelligence, academic ability and personality. Personality and individual differences, 23 (5), 809-814.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T. & Furnham, A. (2004). A possible model for understanding the personality-intelligence interface. British Journal of Psychology, 95, 249-264.

Moutafi, J., Furnham, A. & Crump, J. (2002). Demographic and personality predictors of intelligence: A study using the NEO-personality inventory and the

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. European Journal of Personality, 17, 79-94.

Dr. Merav Hami, a psychologist, graduate of an occupational track, serves as the professional director and heads the development team of the system since its establishment. Merav's doctorate researches how intelligence is expressed in everyday life. During its writing, she developed a unique questionnaire that examines how our intelligence is expressed in practice.

We would be happy to hear your opinion!

LogiPass has dozens of additional articles dealing with issues of screening tests, career guidance and other interesting issues from the world of work.